morning in the garden

O heart !

My tree is full of small birds,

red flowers.

I am below the level of the bee,

the wingbeat of the wren.

A new robin dapples through his

never-ending blue, green.

My tree flowers

beat red like hearts

in warm rings.

© Chris Murray 2016, 2020

Published ANU #48 (ISSUU)

Online URL https://issuu.com/amosgreig/docs/anu_48, Edited by Amos Grieg

Published in translation Şiirden #37, Turkish translation, Müesser Yeniay

Collected Empty House Anthology, Doire Press, 2021, Edited by Nessa O'Mahony, Alice Kinsella.

Online URL https://bit.ly/3m4R9gE

Tag: alice kinsella

-

-

‘Hinnerup’ by Jess McKinney

.

sewing after so long

i wonder if there exists a song

a glass of water warmed in the sun

for each age she’s ever been

all the taps here run scalding

following the dregs of wine

flowing from hot water factories

tell me about her lover

stagnant on the periphery

who lived three towns away

making it harder to soak

she would travel hours to him

the wilting orchids

every other weekend

softening on the windowsill

found sanctuary with his family

reaching up into the day

young and in love

delicate and deliberate

i’d like to know how she felt

like grandmother’s thin fingers

on the birthday that I learned to hate

shaking but capable

the night i faked to get awayHinnerup is © Jess McKinney

Jess Mc Kinney is a queer feminist poet, essayist and English Studies graduate of UCD. Originally from Inishowen, Co. Donegal, she is now living and working in Dublin city, Ireland. Her writing is informed by themes such as sexuality, memory, nature, relationships, gender, mental health and independence. Often visually inspired, she seeks to marry pictorial elements alongside written word. Her work has been previously published in A New Ulster, Impossible Archetype, HeadStuff, In Place, Hunt & Gather, Three fates, and several other local zines.

Jess Mc Kinney is a queer feminist poet, essayist and English Studies graduate of UCD. Originally from Inishowen, Co. Donegal, she is now living and working in Dublin city, Ireland. Her writing is informed by themes such as sexuality, memory, nature, relationships, gender, mental health and independence. Often visually inspired, she seeks to marry pictorial elements alongside written word. Her work has been previously published in A New Ulster, Impossible Archetype, HeadStuff, In Place, Hunt & Gather, Three fates, and several other local zines.‘Prime’ by Peggie Gallagher

It is midwinter.

Your hands are chilled.

I lift you,

gather your first whimpers onto my pillow,

knowing as much by instinct as touch of skin.We lie here amazed at the dark,

aware of the house sleeping around us,

the quiet patterns of breath.

Outside, the snow lies thick.In this landscape of wild skies

and running tides,

and mornings lit with rapture,

I think

I must have been falling most of my life

to land here temple to temple

in this pre-dawn calm,

this kinshipof breath with breath

your hands cupped in my palms.Prime Is © Peggie Gallagher

Peggie Gallagher’s collection, Tilth was published by Arlen House in 2013. Her work has been published in numerous journals including Poetry Ireland, Force 10, THE SHOp, Cyphers, Southword, Atlanta Review, and Envoi. In 2011 she was shortlisted for the Gregory O’Donoghue International Poetry Competition. In 2012 she won the Listowel Writers’ Week Poetry Collection. In 2018 she is the only Irish poet on the Strokestown International poetry competition shortlist. Peggie Gallagher’s work was facilitated by Paul O’Connor.

Peggie Gallagher’s collection, Tilth was published by Arlen House in 2013. Her work has been published in numerous journals including Poetry Ireland, Force 10, THE SHOp, Cyphers, Southword, Atlanta Review, and Envoi. In 2011 she was shortlisted for the Gregory O’Donoghue International Poetry Competition. In 2012 she won the Listowel Writers’ Week Poetry Collection. In 2018 she is the only Irish poet on the Strokestown International poetry competition shortlist. Peggie Gallagher’s work was facilitated by Paul O’Connor.Author image: Southword / Arlen House

‘Linen’ by Finnuala Simpson

A candied calligraphy of colours, I said

That I would change the sheets later.

And I said also that I could handle it but I could not, and will I fry for that?

I may, but only if you return.The stink of sheep hangs on me like wisdom.

You leave in a blur and your bag is heavy with spices,

I hope I do not let you back again.

It depends on my resolve, and on whether the seasons let me float.I’ll take myself running for the friction of denial,

Cross my legs under the tables of the library.

I’ll spin yarns and wear black and eat fruit in the evenings,

Till I’m taller and more thoughtful than I have been before.And I’ll try harder, too.

Kindness is like witchcraft, it must be brewed and stirred,

Mulled over in secret with the herb scent of the night.

If it threatens to drown you, you must set yourself on fire.Do you think of me? Or am I a stop-gap to you?

I marveled at you on the phone when you were talking like a man,

Not laughing or stroking like you laugh and stroke at me.

Talking figures like your car was a woman,

You said fuck it we will fix the white van instead

For by the time the summer comes you will be traveling.I changed my sheets and they were smeared

Sprinkled with both blood and mould.

But washed away now, and quietly, while you are asleep and going south.Linen is © Finnuala Simpson

Finnuala Simpson is a twenty year old English and history student based in West Cork. In her free time she likes to write, cook, and walk as close to the sea as she can get.

‘June’ by Geraldine Plunkett Dillon

I fill my heart with stores of memories,

Lest I should ever leave these loved shores;

Of lime trees humming with slow drones of bees,

And honey dripping sweet from sycamores.Of how a fir tree set upon a hill,

Lifts up its seven branches to the stars;

Of the grey summer heats when all is still,

And even grasshoppers cease their little wars.Of how a chestnut drops its great green sleeve,

Down to the grass that nestles in the sod;

Of how a blackbird in a bush at eve,

Sings to me suddenly the praise of God.June is © Geraldine Plunkett Dillon

The text of Magnificat and images associated with Geraldine Plunkett’s Dillon’s historical and cultural work were kindly sent to me by her great-granddaughter Isolde Carmody and I am very grateful for them. I am delighted to add Geraldine to my indices at Poethead. I hope that this page will increase interest in her work. Excerpts from the Preface to the 2nd edition of All In The Blood, memoirs of Geraldine Plunkett Dillon, edited by Honor Ó Brolcháin,“My greatest regret throughout the process has been how little credit she gives herself, for example she does not mention a paper she gave in the Royal Irish Academy in 1916 or her contribution to the article on dyes in Encyclopedia Britannica or her volume of poetry, Magnificat, or contributing to the Book of St Ultan, or being a founder member of Taibhdhearc na Gaillimhe (the masks of Tragedy and Comedy she made for the Gate theatre are now on a wall in the Taibhdhearc) and the Galway Art Club, where she exhibited for years, or making costumes for Micheál Mac Liammóir in 1928, or being responsible for Oisín Kelly deciding to become a sculptor – he was one of very many who said that she enabled them to do the right thing for their own fulfillment. When she wrote it was in order to provide a history of her times and an insight into what made her family so strange. Like many of her generation she did not write much about her own feelings and her humourous and optimistic nature does not really come through in her writing. I would like to have been able to put that in but could not in all faith do so. “ It is also worth noting that Joe (Joseph Plunkett) named her as literary executor, and she edited his Collected Poems in 1916

‘At the door’ by Eva Griffin

Now, watch as I hang in the air

tempting as a sunset

and just as long.

Storms are not inclined to wait;

better to spill my secret wilderness

as I leave this love,

sucking light out of your blue.At the door is © Eva Griffin

Eva Griffin is a poet living in Dublin and a UCD graduate. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in Tales From the Forest, All the Sins, ImageOut Write, Three Fates, The Ogham Stone, HeadStuff, and New Binary Press

Eva Griffin is a poet living in Dublin and a UCD graduate. Her work has been published or is forthcoming in Tales From the Forest, All the Sins, ImageOut Write, Three Fates, The Ogham Stone, HeadStuff, and New Binary Press‘Cooking Chicken’ by Alice Kinsella

Pink is the colour of life

of new babies’ wet heads

and open screaming mouths.Pink is the rose hip of a woman at the heart

of what’s between her hips

and the tip of my tongue between bud lips.There’s the hint of pink on daisies

when they open their petals to say

hello to the birth of a new day.But pink is also the colour of death

as the knife slides between the flesh

and separates it into food.Pink is a suggestion of sickness when I pierce the skin,

dissect the sinews, glimpse the tint of it and turn

it to the heat to kill the pink and the possibility.It’s the quiver of the comb atop feathers,

and the neck as it’s sliced from the body

by the executioner’s axe.It’s the colour of cunt

and the hint in the sky

when the cock crows.Cooking Chicken is © Alice Kinsella

Alice Kinsella was born in Dublin and raised in the west of Ireland. She holds a BA(hons) in English Literature and Philosophy from Trinity College Dublin. Her poetry has been widely published at home and abroad, most recently in Banshee Lit, Boyne Berries, The Lonely Crowd and The Irish Times. Her work has been listed for competitions such as Over the Edge New Writer of the Year Competition 2016, Jonathan Swift Awards 2016, and Cinnamon Press Pamphlet Competition 2017. She was SICCDA Liberties Festival writer in residence for 2017 and received a John Hewitt bursary in the same year. Her debut book of poems, Flower Press was published in 2018 by The Onslaught Press.

Alice Kinsella was born in Dublin and raised in the west of Ireland. She holds a BA(hons) in English Literature and Philosophy from Trinity College Dublin. Her poetry has been widely published at home and abroad, most recently in Banshee Lit, Boyne Berries, The Lonely Crowd and The Irish Times. Her work has been listed for competitions such as Over the Edge New Writer of the Year Competition 2016, Jonathan Swift Awards 2016, and Cinnamon Press Pamphlet Competition 2017. She was SICCDA Liberties Festival writer in residence for 2017 and received a John Hewitt bursary in the same year. Her debut book of poems, Flower Press was published in 2018 by The Onslaught Press. -

Periwinkle (I)

Your fingers unveiled the shell,

like the unwrapping of a present.

Little twirls on the bright jewel found

amongst greys, greens, muddied sand.Words whistling through tooth gaps,

excitement brought by being somewhere new.

Finding me still at home, unchanged,

ready to believe any adventure.Curled sunshine shell like the buttercup

reflection on your chin,

shimmering summer sea surface,

as we held our fingers too close

to each other’s faces for the first time.The swirl of it, poised to spring,

and unravel into something new,

something other than the little yellow

shell, carried home from your holidays,

to share a little of the sunlight with me.Periwinkle was originally published in The Galway Review

Tír na nÓg

In lieu of history classes we learned legends of warriors,

fierce fighting Fianna we were sure lived in our blood.Neart ár ngéag

We waved ash branches for swords,

flew down hills on steeds with wheels,

foraged berries, scaring magpies with screams,

cleared the stream in one leap — this was our land.My favourite was the story

of Oisín, little deer bard boy,

bravest of band of brothers,

tempted by beauty and promises,

he left for the land of the young.We watched the tape of Into the West

while eating beans on toast

we pretended we’d cooked in camp fires,

you laughing at my Dublin dialect

dissolving with Wild West warrior words.Beart de réir ár mbriathar

Ears hanging on the telling of legends

round camp fires, the memories of

stories, the bravery of Oisín the poet

prince and his fairy love laying siege

to time with their eternal youth.You ran home in half-dark before bedtime,

I watched the film to the end,

read the whole story in the illustrated booklearning that no amount of love

could keep him in the land without death

that the call of age would always test.Glaine ár gcroí

One snap of the rope, the saddle strap broke,

the fall of a warrior that could not keep fighting.Tír na nÓg was originally published on the Rochford Street Review

The ends of it

I want to watch the clouds melt into Croagh Patrick,

sitting on the stone wall of my parents’ drive,

one more summer night that is miles past bed time.I want to watch tadpoles grow legs

while they still have tails, trap them

in a jar and marvel at their ability

to be at once both and neither.I want to watch the calves stop being cute

until only syrupy brown eyes remind us

they were ever splayed bloody and new on the floor

of the barn while we looked on in fleece lined pyjamas

and wellies, red-eyed and giddy.I want to watch you smoke your first cigarette,

feel the burn of it when I try,

and the wet of your mouth on the tip of it,

want to dig a hole in the field and bury the ends of it.

Bury it deep,

where no one will find it.The ends of it was originally published in The Stony Thursday Book

Cooking Chicken

Pink is the colour of life

of new babies’ wet heads

and open screaming mouths.Pink is the rose hip of a woman at the heart

of what’s between her hips

and the tip of my tongue between bud lips.There’s the hint of pink on daisies

when they open their petals to say

hello to the birth of a new day.But pink is also the colour of death

as the knife slides between the flesh

and separates it into food.Pink is a suggestion of sickness when I pierce the skin,

dissect the sinews, glimpse the tint of it and turn

it to the heat to kill the pink and the possibility.It’s the quiver of the comb atop feathers,

and the neck as it’s sliced from the body

by the executioner’s axe.It’s the colour of cunt

and the hint in the sky

when the cock crows.Cooking Chicken was originally published in Banshee Lit (Spring 2017)

When

When you can say the words that are not listened to

But keep on saying them because you know they’re true;

When you can trust each other when all men doubt you

And from support of other women make old words new;

When you can wait, and know you’ll keep on waiting

That you’ll be lied to, but not sink to telling lies;

When you know you may hate, but not be consumed by hating

And know that beauty doesn’t contradict the wise;

When you can dream – and know you have no master;

When you can think – let those thoughts drive your aim;

When you receive desire and abuse from some Bastard

And treat both manipulations just the same;

When you hear every trembling word you’ve spoken

Retold as lies, from a dishonest heart;

When you have had your life, your body, broken

But stop, breathe, and rebuild yourself right from the start;

When you can move on but not forget your beginnings

And do what’s right no matter what the cost;

Lose all you’ve worked for, forget the aim of winning

And learn to find the victory in your loss;

When you can see every woman struggle – to

create a legacy, for after they are gone

And work with them, when nothing else connects you

Except the fight in you which says: ‘Hold on!’

When you can feel the weight of life within you

But know that you alone are just enough;

When you know not to judge on some myth of virtue

To be discerning, but not too tough;

When you know that you have to fight for every daughter

Even though you are all equal to any son;

When you know this, but still fill your days with laughter

You’ll have the earth, because you are a woman!

When was originally published in The Irish Times for International Women’s Day 2017Making Pies

We picked blackberries

after school for three weeks

before dressing up and dreading

the púca’s poison spit.We munched as we gathered,

were left with only half our spoils,

licked our fingers dry of juice,

we always came home late.To protect their labours the briars

attacked and tore into soft finger tips.

I delved into the gushing wound, lapped up

the coppery flow and sucked out the hidden prick.I always said it didn’t hurt.

There was an orchard in my back garden

there we could pick our second ingredient;

Apples, six apiece to make a pie.They were high up, buried in the auburn curls of autumn.

You’d give me a boost, half the time we’d fall over,

and stain our trousers with the dewy evening lawn.You always said it didn’t hurt.

Once, they were sparse: a bad year my mother said,

so she bought cooking apples from the new Tesco in Town.

I had to peel the stickers off before she skinned them.

That was the year I learned to use the sharp knives,

and we didn’t go trick or treating any more.An earlier version of Making Pies was published on Poethead in 2015

Alice Kinsella was born in Dublin and raised in the west of Ireland. She holds a BA(hons) in English Literature and Philosophy from Trinity College Dublin. Her poetry has been widely published at home and abroad, most recently in Banshee Lit, Boyne Berries, The Lonely Crowd and The Irish Times. Her work has been listed for competitions such as Over the Edge New Writer of the Year Competition 2016, Jonathan Swift Awards 2016, and Cinnamon Press Pamphlet Competition 2017. She was SICCDA Liberties Festival writer in residence for 2017 and received a John Hewitt bursary in the same year. Her debut book of poems, Flower Press, will be published in 2018 by The Onslaught Press.

‘When’ and other poems are © Alice Kinsella

For more information visit aliceekinsella.com or Facebook.com/AliceEKinsella -

Both a page and performance poet, Anne Tannam’s work has appeared in literary journals and magazines in Ireland and abroad. Her first book of poetry Take This Life was published by WordOnTheStreet in 2011 and her second collection Tides Shifting Across My Sitting Room Floor will be published by Salmon Poetry in Spring 2017. She has performed her work at Lingo, Electric Picnic, Blackwater & Cúirt Literary Festival. Anne is co-founder of the Dublin Writers’ Forum.

Both a page and performance poet, Anne Tannam’s work has appeared in literary journals and magazines in Ireland and abroad. Her first book of poetry Take This Life was published by WordOnTheStreet in 2011 and her second collection Tides Shifting Across My Sitting Room Floor will be published by Salmon Poetry in Spring 2017. She has performed her work at Lingo, Electric Picnic, Blackwater & Cúirt Literary Festival. Anne is co-founder of the Dublin Writers’ Forum.

“The World Reduced to Sound” by Anne Tannam

Lying in my single bed

a childhood illness for company

the world reduced to sound.

Behind my eyes the darkness echoed

inside my chest uneven notes

rattled and wheezed.

Beyond my room a floorboard creaked

a muffled cough across the landing

grew faint and faded away

My hot ear pressed against the pillow

tuned into the gallop of tiny hooves

then blessed sleepy silence.

In the morning

steady maternal footsteps

sang on the stairs.

I loved that song.

The World Reduced to a Sound is © Anne Tannam and was published in ‘Take This Life’ (WordOnTheStreet 2011) Nicki Griffin grew up in Cheshire but has lived in East Clare since 1997. Her debut collection of poetry, Unbelonging, was published by Salmon Poetry in 2013 and was shortlisted for the Shine/Strong Award 2014 for best debut collection. The Skipper and Her Mate (non-fiction) was published by New Island in 2013. She won the 2010Over the Edge New Poet of the Year prize, was awarded anArts Council Literature Bursary in 2012 and has an MA in Writing from National University of Ireland, Galway. She is co-editor of poetry newspaper Skylight 47.

Nicki Griffin grew up in Cheshire but has lived in East Clare since 1997. Her debut collection of poetry, Unbelonging, was published by Salmon Poetry in 2013 and was shortlisted for the Shine/Strong Award 2014 for best debut collection. The Skipper and Her Mate (non-fiction) was published by New Island in 2013. She won the 2010Over the Edge New Poet of the Year prize, was awarded anArts Council Literature Bursary in 2012 and has an MA in Writing from National University of Ireland, Galway. She is co-editor of poetry newspaper Skylight 47.

“Nantwich Dusk” by Nicki Griffin

The canopy of dark stars

stretches low across the rooftops,

half a million

tiny heartbeats.

We watch from the bay window,

my father and I,

as church bells ring

for evensong

and darkness closes.

Starlings tighten,

fold into clouds,

shapes of smoke

convulse and change

as though a magician,

wand attached

to the tail of the flock,

has flicked her wrist.

Across the road

birds break rank,

funnel into trees,

a diving platoon

of black handkerchiefs.

Nantwich Dusk is © Nicki Griffin Lorna Shaughnessy was born in Belfast and lives in Co. Galway, Ireland. She has published three poetry collections, Torching the Brown River, Witness Trees, and Anchored (Salmon Poetry, 2008 and 2011 and 2015), and her work was selected for the Forward Book of Poetry, 2009. Her poems have been published in The Recorder, The North, La Jornada (Mexico) and Prometeo (Colombia), as well as Irish journals such as Poetry Ireland, The SHop and The Stinging Fly. She is also a translator of Spanish and South American Poetry. Her most recent translation was of poetry by Galician writer Manuel Rivas, The Disappearance of Snow (Shearsman Press, 2012), which was shortlisted for the UK Poetry Society’s 2013 Popescu Prize for translation.

Lorna Shaughnessy was born in Belfast and lives in Co. Galway, Ireland. She has published three poetry collections, Torching the Brown River, Witness Trees, and Anchored (Salmon Poetry, 2008 and 2011 and 2015), and her work was selected for the Forward Book of Poetry, 2009. Her poems have been published in The Recorder, The North, La Jornada (Mexico) and Prometeo (Colombia), as well as Irish journals such as Poetry Ireland, The SHop and The Stinging Fly. She is also a translator of Spanish and South American Poetry. Her most recent translation was of poetry by Galician writer Manuel Rivas, The Disappearance of Snow (Shearsman Press, 2012), which was shortlisted for the UK Poetry Society’s 2013 Popescu Prize for translation.

“Moving Like Anemones” by Lorna Shaughnessy

(Belfast, 1975)

I

I cannot recall if you met me off the school bus

but it was winter, and dark in the Botanic Gardens

as we walked hand in hand to the museum.

Too young for the pub, in a city of few neutral spaces

this was safe, at least, and warm.

The stuffed wolfhound and polar-bear were no strangers,

nor the small turtles that swam across the shallow pool

where we tossed pennies that shattered our reflected faces.

We took the stairs to see the mummy

but I saw nothing, nothing at all, alive

only to the touch of your fingers seeking mine,

moving like anemones in the blind depths.

II

Disco-lights wheeled overhead,

we moved in the dark.

Samba pa ti, a birthday request,

the guitar sang pa mí, pa ti

and the world melted away:

the boys who stoned school buses,

the Head Nun’s raised eyebrow.

Neither ignorant nor wise,

we had no time to figure out

which caused more offence,

our religions or the four-year gap between us.

I was dizzy with high-altitude drowning,

that mixture of ether and salt,

fourteen and out of my depth.

III

The day was still hot when we stepped

into cool, velvet-draped darkness.

I wore a skirt of my sister’s from the year before

that swung inches above cork-wedged sandals.

You were all cheesecloth and love-beads.

I closed my eyes in surrender

to the weight of your arm on my shoulders,

the tentative brush of your fingers

that tingled on my arm, already flushed

by early summer sun.

Outside the cinema I squinted,

strained to adjust to the light

while you stretched your long limbs like a cat.

You were ripe for love and knew it;

I blushed and feared its burning touch.

“Moving Like Anemones” Is © Lorna O’Shaugnessy Maria Wallace (Maria Teresa Mir Ros) was born in Catalonia, but lived her teenage years in Chile. She later came to Ireland where she has now settled. She has a BA in English and Spanish Literature, 2004, an MA in Anglo-Irish Literature, 2005. She won the Hennessy Literary Awards, Poetry Section, 2006. Her work has been published widely in Ireland, England, Italy, Australia and Catalonia. Winner of The Scottish International Poetry Competition, The Oliver Goldsmith Competition, Cecil Day Lewis Awards, Moore Literary Convention, Cavan Crystal Awards, William Allingham Festival. She participated in the ISLA Festival (Ireland, Spain and Latin America), 2015, and has published Second Shadow, 2010, and The blue of distance, 2014, two bilingual collections (English – Catalan), a third one to come out within the year. She has taught Spanish, French, Art and Creative Writing. She facilitates Virginia House Creative Writers,’ a group she founded in 1996, and has edited three volumes of their work.

Maria Wallace (Maria Teresa Mir Ros) was born in Catalonia, but lived her teenage years in Chile. She later came to Ireland where she has now settled. She has a BA in English and Spanish Literature, 2004, an MA in Anglo-Irish Literature, 2005. She won the Hennessy Literary Awards, Poetry Section, 2006. Her work has been published widely in Ireland, England, Italy, Australia and Catalonia. Winner of The Scottish International Poetry Competition, The Oliver Goldsmith Competition, Cecil Day Lewis Awards, Moore Literary Convention, Cavan Crystal Awards, William Allingham Festival. She participated in the ISLA Festival (Ireland, Spain and Latin America), 2015, and has published Second Shadow, 2010, and The blue of distance, 2014, two bilingual collections (English – Catalan), a third one to come out within the year. She has taught Spanish, French, Art and Creative Writing. She facilitates Virginia House Creative Writers,’ a group she founded in 1996, and has edited three volumes of their work.

“Under the shadow of birds” by Maria Wallace

Black birds,

she thinks they are ravens,

hover over her

for the past eighteen years.

Their coarse croaking cries

drown all other sounds;

dark plumage shines

as they circle around

ready to destroy

the little she still has:

a neat house for two. Neat.

For two. Even under attack.

Not a speck of dust –

the aroma of fresh baking

rejoicing through the house,

though, the birds’ shadows stab,

their long bills tear her innards.

One May afternoon in the cul-de-sac.

Her toddler son in a group

playing Simon Says,

and Hop, Skip and Jump

a few feet from them.

A screech of tyres always tells a story.

Her doctor said

another baby would help the healing.

The first flock of black birds swooped down

when her husband said:

Another baby?

No way! You couldn’t look after

the one you had! Kimberly Campanello was born in Elkhart, Indiana. She now lives in Dublin and London. She was the featured poet in the Summer 2010 issue of The Stinging Fly, and her pamphlet Spinning Cities was published by Wurm Press in 2011 . Her poems have appeared in magazines in the US, UK, and Ireland, including nthposition , Burning Bush II, Abridged , and The Irish Left Review . Her books are Consent published by Doire Press, and Strange Country Published by Penny Dreadful (2015) ZimZalla will publish MOTHERBABYHOME, a book of conceptual poetry in 2016.

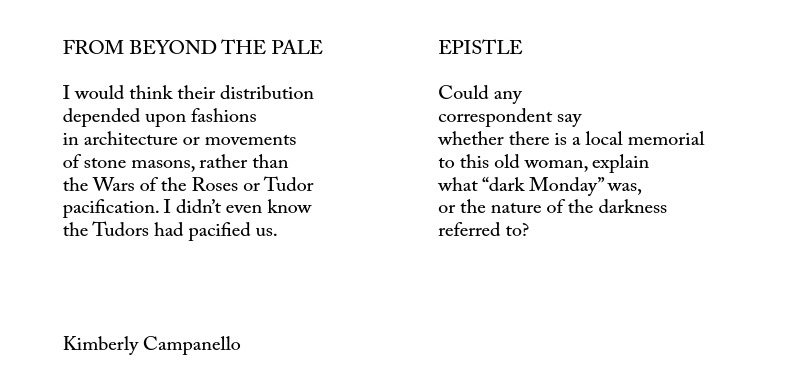

Kimberly Campanello was born in Elkhart, Indiana. She now lives in Dublin and London. She was the featured poet in the Summer 2010 issue of The Stinging Fly, and her pamphlet Spinning Cities was published by Wurm Press in 2011 . Her poems have appeared in magazines in the US, UK, and Ireland, including nthposition , Burning Bush II, Abridged , and The Irish Left Review . Her books are Consent published by Doire Press, and Strange Country Published by Penny Dreadful (2015) ZimZalla will publish MOTHERBABYHOME, a book of conceptual poetry in 2016.Poems from “Strange Country” by Kimberly Campanello

Katie Donovan has published four books of poetry, all with Bloodaxe Books, UK. Her first, Watermelon Man appeared in 1993. Her second, Entering the Mare, was published in 1997; and her third, Day of the Dead, in 2002. Her most recent book, Rootling: New and Selected Poems appeared in 2010. Katie Donovan’s fifth collection of poetry, Off Duty will be published by Bloodaxe Books in September 2016. She is currently working on a novel for children.

She is co-editor, with Brendan Kennelly and A. Norman Jeffares, of the anthology, Ireland’s Women: Writings Past and Present (Gill and Macmillan, Ireland; Kyle Cathie, UK, 1994; Norton & Norton, US, 1996). She is the author of Irish Women Writers: Marginalised by Whom? (Raven Arts Press, 1988, 1991). With Brendan Kennelly she is the co-editor of Dublines (Bloodaxe, 1996), an anthology of writings about Dublin.

Her poems have appeared in numerous periodicals and anthologies in Ireland, the UK and the US. She has given readings of her work in many venues in Ireland, England, Belgium, Denmark, Portugal, the US and Canada. She has read her work on RTÉ Radio One and on BBC Radio 4 and BBC Radio 3. Her short fiction has appeared in The Sunday Tribune and The Cork Literary Review.

“Off Duty” by Katie Donovan

Is my face just right,

am I looking as a widow should?

I pass the funeral parlour

where four weeks ago

the ceremony unfurled.

Now I’m laughing with the children.

The director of the solemn place

is lolling out front, sucking on a cigarette.

We exchange hellos,

and I blush, remembering

how I still haven’t paid the bill,

how I nearly left that day

with someone else’s flowers.

Off Duty is © Katie Donovan first published in The Irish Times, 2014, by Poetry Editor Gerry Smyth Alice Kinsella is a young writer living in Dublin. She writes both poetry and fiction and has been published in a variety of publications, including Headspace magazine and The Sunday Independent. She is in her final year of English Literature at Trinity College Dublin and currently working on her first novel.

Alice Kinsella is a young writer living in Dublin. She writes both poetry and fiction and has been published in a variety of publications, including Headspace magazine and The Sunday Independent. She is in her final year of English Literature at Trinity College Dublin and currently working on her first novel.

“Pillars” by Alice Kinsella

There were seven

if I recall correctly

in our townland

When we were young

three now

or there were anyway

last time I was home.

You’ll find them in any house

round those parts

with the leaky roof and the mongrel

who tore open the postman’s leg.

There’s Paig who lives by the sun

after the ESB charged him too much

ao he ripped the wires out

of his six generation old shell of stone.

Whose rippled forehead

and bloody eyes gestured

as we flew by on our rusty bikes.

We never stopped

so’s not to be a bother.

There’s Jon Joe then with the single glazing

and the tractor older than any child

he might have had

would be now

had he had one.

He’s the one we all know has the punts

stuffed under the mattress.

The one that never sponsored our sports days.

And then there’s Tom.

Old Tom not as old as you may think.

who lost his namesake

to a kick of the big blue bull.

They weren’t talking

at the time

but he sold the bull afterwards

and the money went on the bachelor pad

because She kept the house.

You’ll find them anywhere around those parts

at the right time

once you know the right time

that is.

They’re the shadows of the women

these men.

They’re the welcome and g’afternoon

at the church doors

holding up the walls

later holding up the bar

(Neither in nor out)

You’ll know them by the cut of their turf

and the cut of their jip

by the stretch of their land

and the hunch in their backs.

There’s the grit in their voice

and the light in the eye.

And when they die

they’ll be called pillars

of the community

but we didn’t notice them crumble

and we’ll soon forget they’re gone.

“Pillars” is © Alice Kinsella An Index of Women Poets

An Index of Women Poets

Contemporary Irish Women Poets -

Sea walk.

A grey day

Bitter winter

Biting wind

And there was us

We got our shoes

Wet and our toes

Wrinkled

In our socks

The sand clumped

Our fingers curled

And I tasted salt

Coating your lips

Goose bumps rose

On our arms

And the hairs stood stiff

Like tiny white flags

The air licked wet

We bundled coats tighter

And your fingertips put

Bruises on my skin

You said we’d come back

When the weather

Turned

And Wade barefoot.

The weather turned all right.

But we never did,

Did we?

Tea Leaves

Amongst the ghosts

Of coffee dates

Gone by

Two old friends met

to share a brew and some moments.

They sat on rickety chairs

out of doors in sticky rain.

Shredded tobacco with shaking hands

Into thin bent rollies

And tugged on them to fill their mouths

with anything but words.

Coffee for her and a green tea for him

A long repeated order

a rehearsal of a memory

And do you remember when?

He did.

And how we used to?

She did.

They were great times weren’t they?

They agreed they were.

He tells her he remembers

when she bought those earrings

a flea market wasn’t it?

No it wasn’t she tells him

These were a gift.

Oh.

They were sitting still.

But they knew where they were going.

The cups emptied

the butts smouldered like late night peat

They waited a bit longer

Before paying the bill

Spilling coins on the table like a flood of tears

that just wasn’t coming.

They rose with silent mouths to say

Well

Good luck then

And thanks for it all.

Before dividing paths

They looked smiled again

A shallow curve that didn’t reach the eyes

They brushed hands instead of lips

trading nods instead of love.

Tea Leaves was originally published in The Sunday Independent.

After the storm

The dress I wore was black

Every day for a month

In and out

My mother would steal it as I slept

To run it through the wash

Scrub away the musty smell of sleep

Each day announced itself with light

Breaking through at 5.15, 5. 05. 4.55.

Reaching in, it did not brush the hair from my eyes

With love, a gentle reminder of the world beyond dreams

No, it pushed through with a silent scream

And bolted me awake in one shocking leap of heart

Every day in and out

Wake, shower, walk,

Eat, read, sleep

Repeat

Repeat

Repeat

“take your pill did you remember?”

Yes

“did you remember to take your pill?”

Yes

“don’t forget to take your pill”

I won’t

At night I sit by the window let air in

To merge with Turf and tobacco scent in my hair

Shorter than before

“less hassle now isn’t it?”

Eyelids droop “no more caffeine or vodka now no”

But they didn’t take my fags at least

There is a calm not before but after

Unlike any other

No longer an anticipation of release

Lacking the fire, the fury, the fear

Now there’s a deathly droll of life

On repeat- on repeat- on repeat.

The Stranger.

The daisies in her hair wept

Each petal curling at the end

A flick of a goodbye to the day

The sea licked her little toes

And her mum watched on

Half distracted

As mums must be.

Her blonde plait

Jolted and darted

Down her back

Like a snake.

Her new teeth like tiny fangs

Jabbed through gums

Her tooth fairy money

Still jingled in her

First big girl purse.

The sun lay heavy

dropping towards the sea.

He watched from his perch of a rock

And thought how nice it was

To see the young

Enjoying the beach.

“Mister why are you wearing shoes?”

“I’m not going into the sea.”

“and what’s that stick for?”

“it helps me when I walk.”

She showed him the shells

That she’d collected

“do you know their names?”

She shook her head

So he told her the names of all the shells

And the creatures who used to live in them

He thought of his daughter

And how she’d learned

The names of the birds

Out on this beach

So long ago

When she was small too.

Her mother almost dropped her phone

And hurried over.

She couldn’t believe

How little attention

She’d been paying

To her little girl.

“come away from that man

You’re not to talk to strangers.”

Her mother didn’t look him in the eye

Just scowled

And muttered the word

All parents fear.

He tried not to take it to heart.

He had a daughter too.

He’d been the same

When she was that age.

He’d been a police man.

Back in his day.

He knew the things all parents knew.

He loved his daughter.

She lived in Australia now.

Her picture was above the mantel at home.

He loved his own daughter.

He’d never hurt kids.

Pillars

There were seven

if I recall correctly

in our townland

When we were young

three now

or there were anyway

last time I was home.

You’ll find them in any house

round those parts

with the leaky roof and the mongrel

who tore open the postman’s leg.

There’s Paig who lives by the sun

after the ESB charged him too much

ao he ripped the wires out

of his six generation old shell of stone.

Whose rippled forehead

and bloody eyes gestured

as we flew by on our rusty bikes.

We never stopped

so’s not to be a bother.

There’s Jon Joe then with the single glazing

and the tractor older than any child

he might have had

would be now

had he had one.

He’s the one we all know has the punts

stuffed under the mattress.

The one that never sponsored our sports days.

And then there’s Tom.

Old Tom not as old as you may think.

who lost his namesake

to a kick of the big blue bull.

They weren’t talking

at the time

but he sold the bull afterwards

and the money went on the bachelor pad

because She kept the house.

You’ll find them anywhere around those parts

at the right time

once you know the right time

that is.

They’re the shadows of the women

these men.

They’re the welcome and g’afternoon

at the church doors

holding up the walls

later holding up the bar

(Neither in nor out)

You’ll know them by the cut of their turf

and the cut of their jip

by the stretch of their land

and the hunch in their backs.

There’s the grit in their voice

and the light in the eye.

And when they die

they’ll be called pillars

of the community

but we didn’t notice them crumble

and we’ll soon forget they’re gone.

Making Pies

We would pick black berries

Every day after school

For three weeks before

Dressing up and dreading

Pooka’s poison spit.

We’d munch as we gathered

be left with only half our winnings

lick our fingers dry of juice

and always come home late.

To protect their labours

the briars would attack

and tear into soft finger tips.

I’d delve delicately into

the gushing wound,

lap up the coppery flow

and suck out the hidden prick.

I’d always say it didn’t hurt.

There was an orchard in my back garden

there we could pick our second ingredient

Apples.

Six a piece to make a pie

They were high up

And buried in the auburn curls of autumn

You’d give me a boost

And half the time we’d fall over

Stain our trousers

With the dewy evening lawn.

You’d always say it didn’t hurt.

One year they were sparse

“a bad year” my mother said

So she bought cooking apples

From the new Tesco in Town

And I had to peel the stickers

Off before she skinned them.

That was the year I learned to

Use the sharp knives

And we didn’t go trick or treating

Anymore.

“Pillars” and other poems are written by and © Alice Kinsella. Alice Kinsella is a young writer living in Dublin. She writes both poetry and fiction and has been published in a variety of publications, including Headspace magazine and The Sunday Independent. She is in her final year of English Literature at Trinity College Dublin and currently working on her first novel.

Alice Kinsella is a young writer living in Dublin. She writes both poetry and fiction and has been published in a variety of publications, including Headspace magazine and The Sunday Independent. She is in her final year of English Literature at Trinity College Dublin and currently working on her first novel.